Let's go slowly. Here's a better comparison (note that mleftright is only about fixing the horizontal spacing and does nothing different from using \left and \right as far as choosing a size is concerned).

\documentclass{article}

%\usepackage{newtxtext,newtxmath} % With newtx and pdflatex, everything is equally bombastic.

\begin{document}

\(\left(\check{h}\right)\)

\( (\check{h}) \)

\( \bigl(\check{h}\bigr) \)

\( \Bigl(\check{h}\Bigr) \)

\(\left(\hat{h}\right)\)

\( (\hat{h}) \)

\( \bigl(\hat{h}\bigr) \)

\( \Bigl(\hat{h}\Bigr) \)

\end{document}

The tiny difference in height of \hat with respect to \check forces \left and \right to choose the next level in the latter case.

Parentheses are only available at discrete steps: normal, \big, \Big, \bigg and \Bigg. The rules are fairly complicated: there is an interplay of two parameters, \delimitershortfall (a dimension) and \delimiterfactor; the usual values are 5pt for the former (a length) and 901 for the latter (an integer).

If y1 and y2 denote the height and depth of the material to cover, TeX sets y to twice the maximum of the two lengths. If f is the value of \delimiterfactor and d the size of \delimitershortfall, then TeX chooses a delimiter whose (total) size is at least fy/1000 and at least y–d. It's here that the difference in height between \hat and \check comes into play, together with the fact that h is tall. Note that at least is the key: a tiny difference may cause the choice to jump to the next available size. In this case the difference is slightly less than 0.66pt (0.22mm); the value of y is 17.84726pt for \check{h} and 19.16668pt for \hat{h}, so we have that the fences should be at least 16.08038pt for \check{h} and 17.26918pt for \hat{h}: the tiny difference becomes about 1.2pt when the choice of the fences is attempted, which is indeed quite big (the height of h is the main factor).

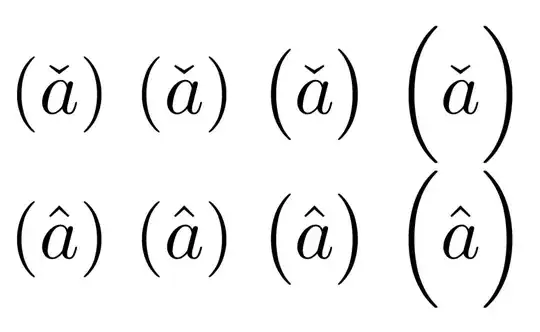

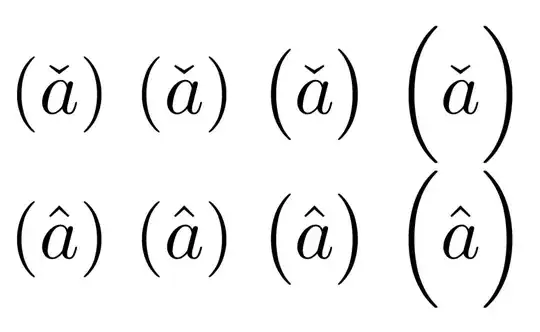

With a instead, we'd get

There's generally no need that the fences cover all the material between them and that's the purpose of the two parameters described above. The availability of fences only at discrete steps is, of course, of hindrance and often the chosen size is too big.

If you look at \( (\hat{h}) \), you see it’s the right size. Maybe \big size could be a choice, but if you look carefully, the fences extend too much below the baseline. Good typography is a craft and requires judgement: automatisms are evil.

\bigl(...\bigr)rather than\left(..\right)(or in this case simply(..)as egreg observes – David Carlisle Jul 03 '17 at 21:43\leftand\rightvery sparingly. Note that$(\hat{h})$has perfectly sized brackets. – egreg Jul 03 '17 at 21:43\delimitershortfalland\delimiterfactorto get the brackets the same size in this case but\leftright have mostly unwanted effect on horizontal space as well and it has to be said, it isn't TeX's best feature. – David Carlisle Jul 03 '17 at 21:51\leftand\right. Type the following in your LaTeX document to see the scales in ascending order:\[ ( \quad \big( \quad \Big( \quad \bigg( \quad \Bigg( \]– Al-Motasem Aldaoudeyeh Jul 03 '17 at 21:53\leftand\rightonly used when they contain fractions (except for a couple of arrays and the absolute value of an integral);\Bigland\Bigrare used for integral evaluation;\bigland\bigrappear sporadically. There's generally no need to adapt the size of the fences. – egreg Jul 03 '17 at 22:18