Consider this code in the TikZ - PGF manual, which uses a macro

% Main code from

% The TikZ - PGF manual

% Author: Till Tantau et al

% Version 3.1.3, released May 9, 2019

% Page 40

\documentclass[tikz]{standalone}

\begin{document}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\def\rectanglepath{-- ++(1cm,0cm) -- ++(0cm,1cm) -- ++(-1cm,0cm) -- cycle}

\draw (0,0) \rectanglepath;

\draw (1.5,0) \rectanglepath;

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{document}

and this one written by me, which uses pic

\documentclass[tikz]{standalone}

\begin{document}

\begin{tikzpicture}

[rectanglepath/.pic={\draw (0,0)--++(1cm,0cm)--++(0cm,1cm)--++(-1cm,0cm)--cycle;}]

\pic at (0,0) {rectanglepath};

\pic at (1.5,0) {rectanglepath};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{document}

Both give us the same output

Observation

Both give the same output. I prefer the latter one, as it is more "TikZ-ish". However, we can always change a code from pic to macro and vice versa, as above (am I wrong – is there a case in which we can't convert?), or draw the same figure using two different codes (this and this for example).

Also, I can't see any aspects in which macros are better than pic. Even arguments: we can also have pic with up to nine arguments with any pattern using /.style args.

In the PGF manual, sometimes I see pic is used, but sometimes a macro is used (it is even used in the title page!). From those examples, I can't figure out in what case I should use a macro and in what case I should use a pic.

Question

It may be quite clear by now.

If I have to draw the same "sub-"picture many times in a TikZ picture, should I use a

picor a macro? And why? Is there any cases in which I must use this one and not the other?

Thanks in advance.

Edit

As for @marmot's nice codes, I have written myself some code (against it) which uses macros

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{tikz}

\begin{document}

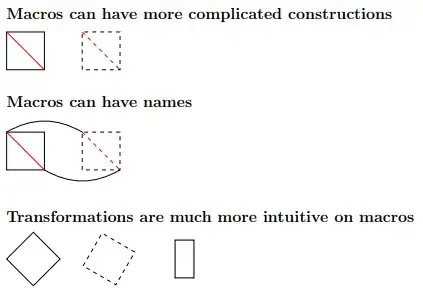

\subsection*{Macros can have more complicated constructions}

\begin{tikzpicture}%[rectanglepath/.pic={\draw (-0.5,-0.5) rectangle ++(1,1);

%\draw[red] (-0.5,0.5) -- (0.5,-0.5);}]

\newcommand\rectanglepath[2][]{\scope[shift={(#2)},#1]\draw (-0.5,-0.5) rectangle ++(1,1);

\draw[red] (-0.5,0.5) -- (0.5,-0.5);\endscope}

%\path (0,0) pic{rectanglepath} (2,0) pic[dashed]{rectanglepath};

\rectanglepath{0,0}

\rectanglepath[dashed]{2,0}

\end{tikzpicture}

\subsection*{Macros can have names}

\begin{tikzpicture}%[rectanglepath/.pic={\draw (-0.5,-0.5) rectangle ++(1,1);

%\draw[red] (-0.5,0.5) coordinate(-tl) -- (0.5,-0.5) coordinate(-br) ;}]

\newcommand\rectanglepath[3][]{\scope[shift={(#2)},#1]\draw (-0.5,-0.5) rectangle ++(1,1);

\draw[red] (-0.5,0.5) coordinate (#3-tl)

-- (0.5,-0.5) coordinate (#3-br);\endscope}

%\path (0,0) pic (A) {rectanglepath} (2,0) pic[dashed] (B) {rectanglepath};

\rectanglepath{0,0}{A}

\rectanglepath[dashed]{2,0}{B}

\draw (A-tl) to[out=30,in=150] (B-tl) (A-br) to[out=-30,in=-150] (B-br);

\end{tikzpicture}

\subsection*{Transformations are much more intuitive on macros}

\begin{tikzpicture}[rectanglepath/.pic={\draw (-0.5,-0.5) rectangle ++(1,1);}]

\newcommand\rectanglepath[2][]

{\scope[shift={(#2)},#1]\draw (-0.5,-0.5) rectangle ++(1,1);\endscope}

%\path (0,0) pic[rotate=45]{rectanglepath} (2,0) pic[dashed,rotate=-30]{rectanglepath}

%(4,0) pic[thick,xscale=0.5]{rectanglepath};

\rectanglepath[rotate=45]{0,0}

\rectanglepath[rotate=-30,dashed]{2,0}

\rectanglepath[thick,xscale=0.5]{4,0}

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{document}