Let's simplify your example (the $-u-u$ is essentially the same as $-2-2$) and ask TeX to show us the math lists before it starts converting them to horizontal lists:

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

\showboxbreadth=20

\showboxdepth=1000

$-2-2 \showlists$. $-\sin(x)-\sin(x) \showlists$.

\end{document}

(you can of course choose other values than 20 and 1000, but if you choose too small values, you won't see the desired contents)

With this, you'll see the following in the log file:

### math mode entered at line 6

\mathbin

.\fam2 ^^@

\mathord

.\fam0 2

\mathbin

.\fam2 ^^@

\mathord

.\fam0 2

This is for the first equation. The \mathbin atoms are your minus signs and the \mathord atoms are the 2s.1

Thanks to Marcel Krüger's comment, we know that the first \mathbin won't really stay a \mathbin, because TeX doesn't allow this at the beginning of a formula (I had forgotten this rule). It will act like a \mathord, as far as spacing goes—see below. So, the small space between unary minus and 2 is the space between two \mathord atoms. The log file will also show the math list built from the second equation:

\mathbin

.\fam2 ^^@

\mathop\nolimits

.\mathord

..\fam0 s

.\mathord

..\fam0 i

.\mathord

..\fam0 n

\mathopen

.\fam0 (

\mathord

.\fam1 x

\mathclose

.\fam0 )

\mathbin

.\fam2 ^^@

\mathop\nolimits

.\mathord

..\fam0 s

.\mathord

..\fam0 i

.\mathord

..\fam0 n

\mathopen

.\fam0 (

\mathord

.\fam1 x

\mathclose

.\fam0 )

As you can see, both minus signs have again been turned into \mathbin atoms (but the one at the beginning of the forumula wil be eventually treated like a \mathord, see above and Marcel Krüger's comment), precisely:

\mathbin

.\fam2 ^^@

The big difference with the first formula is that the \sin is a \mathop, not a \mathord as are the 2s and the us from your example. If you use bracing to make the first \sin(x) a subformula, it becomes wrapped in a \mathord and you get tight spacing (I'm not pronouncing myself on whether this is good typography):

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

\showboxbreadth=20

\showboxdepth=1000

$-2-2$. $-{\sin(x)}-\sin(x) \showlists$.

\end{document}

The first \sin(x) then produces this output in the log file:

### math mode entered at line 6

\mathbin

.\fam2 ^^@

\mathord

.\mathop\nolimits

..\mathord

...\fam0 s

..\mathord

...\fam0 i

..\mathord

...\fam0 n

.\mathopen

..\fam0 (

.\mathord

..\fam1 x

.\mathclose

..\fam0 )

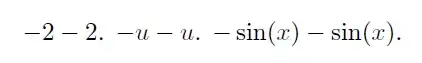

The corresponding rendered output:

Now, thanks to Marcel Krüger's comment, we can explain why the space after the two minus signs starting the formulas are different in the initial example before the 2 and before the \sin: because the minus signs are \mathbin atoms occurring at the start of a formula, TeX actually treats them as \mathord atoms, so according to page 170 of the TeXbook (which is reproduced in this answer of egreg), the space after the first - in $-2-2$ is the space between two consecutive \mathord atoms, i.e., no space at all. On the other hand, the space after the first - in $-\sin(x)-\sin(x)$ is the space between a \mathord on the left and a \mathop on the right, namely a thin space (defined by \thinmuskip, 3mu in plain TeX).

If we wrap the first \sin(x)$ in braces, which makes it a \mathord, we again get the spacing between two consecutive \mathord atoms, i.e., no space at all, as with the 2s and the us.

Footnote

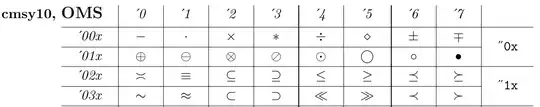

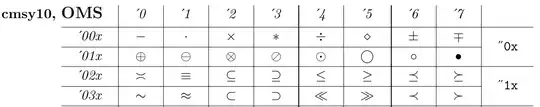

In case you wonder why the minus sign appears as an atom whose nucleus is \fam2 ^^@, here is the explanation. Math family 2 is used by TeX for “basic” math symbols (extensible ones like parentheses, braces, integral signs, \sum, \sqrt, etc., are taken from family 3 instead). The font that is assigned by default to this family is cmsy, whose encoding is called OMS and shown (currently on page 33) in encguide.pdf. As you can see in the following excerpt of cmsy10s' font table:

the glyph in slot 0 of this font is the minus sign. And this is precisely the glyph (presented as

the glyph in slot 0 of this font is the minus sign. And this is precisely the glyph (presented as \fam2 ^^@) in the math list we got from \showlists. Indeed, since the ASCII character with code 0 (aka NUL) is not in the range of printable characters, TeX displays it using its ^^ notation. In this notation, ^^@ represents the character with code 0 because the TeX-internal code for @ is 64, which lies between 64 and 127; therefore, TeX substracts 64 from this internal code, which gives 0. Had the TeX-internal code been between 0 and 63, TeX would have added 64 to the code instead. This rule is described in the TeXbook p. 45. In case you wonder, the “TeX-internal code table” a priori coincides with the ASCII code table for traditional TeX engines:

TeX's internal code is based on the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, known popularly as “ASCII.”

(quote from the TeXbook Appendix C, p. 367, which has a complete table of the encoding).

\!is a negative thin space, just compensating for the thin space in front of the operator. I think you'll find it's not an improvement, though, especially if you drop the parentheses:-\sin xwill look better than-\!\sin x. – Harald Hanche-Olsen Jan 19 '20 at 09:57