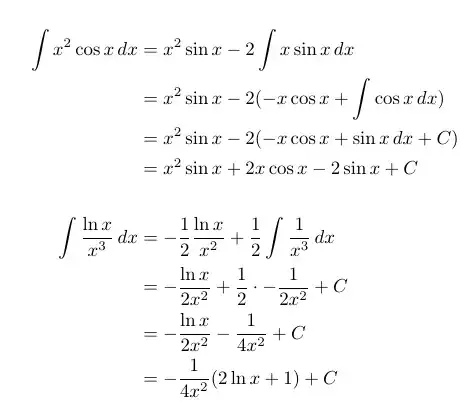

In the snip, we can see that two groups of equations, aligned individually on the within-group = symbols.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{mathtools}

\begin{document}

\begin{enumerate}

\item

$$\begin{aligned}

\int x^2 \cos x \,dx

&= x^2 \sin x - 2 \int x \sin x \,dx

\\ &= x^2 \sin x - 2 (-x \cos x +\int \cos x \,dx)

\\ &= x^2 \sin x - 2 (-x \cos x + \sin x \,dx + C)

\\ &= x^2 \sin x + 2x \cos x - 2\sin x + C

\end{aligned}$$

\item

$$\begin{aligned}

\int \frac{\ln x}{x^3} \,dx

&= -\frac{1}{2} \frac{\ln x}{x^2} +

\frac{1}{2} \int \frac{1}{x^3} \,dx

\\ &= -\frac{\ln x}{2x^2} +

\frac{1}{2} \cdot -\frac{1}{2x^2} + C

\\ &= -\frac{\ln x}{2x^2} - \frac{1}{4x^2} + C

\\ &= -\frac{1}{4x^2}(2\ln x + 1) + C

\end{aligned}$$

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}

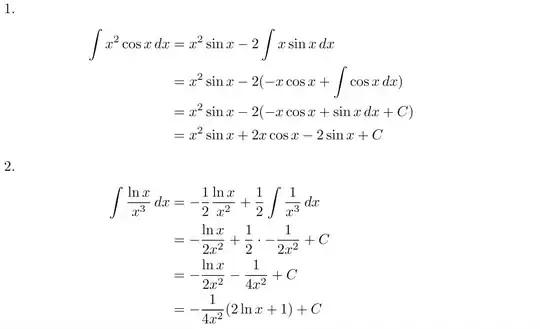

How to align the two groups of equations on the same equal symbol "="?

Like this:

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{mathtools}

\begin{document}

\begin{enumerate}

\item

$$\begin{aligned}

\int x^2 \cos x \,dx

&= x^2 \sin x - 2 \int x \sin x \,dx

\\ &= x^2 \sin x - 2 (-x \cos x +\int \cos x \,dx)

\\ &= x^2 \sin x - 2 (-x \cos x + \sin x \,dx + C)

\\ &= x^2 \sin x + 2x \cos x - 2\sin x + C

\\

\\

\int \frac{\ln x}{x^3} \,dx

&= -\frac{1}{2} \frac{\ln x}{x^2} +

\frac{1}{2} \int \frac{1}{x^3} \,dx

\\ &= -\frac{\ln x}{2x^2} +

\frac{1}{2} \cdot -\frac{1}{2x^2} + C

\\ &= -\frac{\ln x}{2x^2} - \frac{1}{4x^2} + C

\\ &= -\frac{1}{4x^2}(2\ln x + 1) + C

\end{aligned}$$

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}

In this approach, the numbers generated by enumerate are missing, so I'm

wondering are there better ways.

$$ ... $$for displayed equations with LaTeX. Use the LaTeX construct\[ ... \]instead, for a correct vertical spacing. – Bernard Apr 08 '20 at 15:29\intertextlooks promising, as in this answer: Aligning equations, splitted in an enumeration – barbara beeton Apr 08 '20 at 15:42\iteminstructions (encased in\intertextor\shortintertextinstructions) don't have any visible material associated with them. – Mico Apr 08 '20 at 15:50