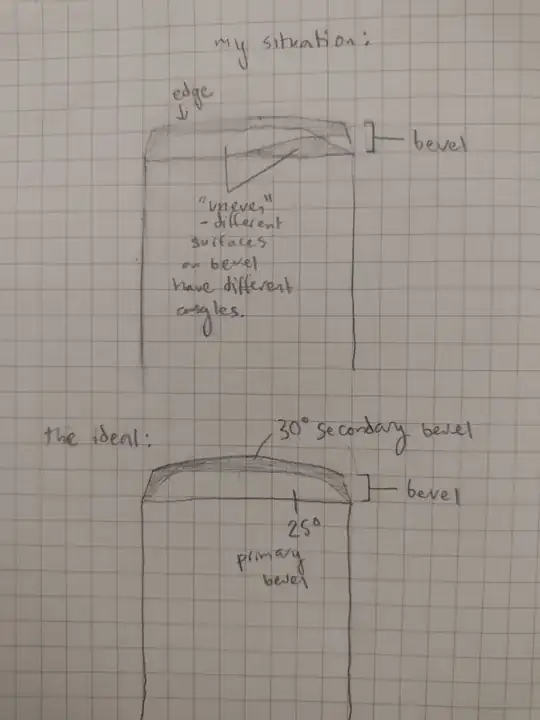

Okay, first thing to mention is that a 25° primary and a 30° secondary are the convention but they're really textbook examples and they don't have to be followed to the letter at all.

Many people who freehand sharpen don't know the angle that they hone at because A, it doesn't matter1, and B, they never measure it. They just know if they lift the iron "this amount" higher they get their usual honing angle and they work on their secondary.

Your edge as-is

Although it's kinda ugly what you have there is perfectly fine. It could maybe do with being a touch more curved, but that's not essential — just some sort of noticeable curve to the edge is what's important for a jack2, not the exact curvature or how even it is. This also holds true for scrub planes that have a much more pronounced profile.

Think of it this way, this plane (ditto a scrub) almost always won't be the last to touch the wood, right? So even if each shaving did leave a noticeably uneven groove it doesn't matter because the next plane is going to be the one to flatten off the surface. If this plane is intended to be the last one to touch the wood then an irregular, hand-worked surface is what's intended anyway.

If the worry is not just about aesthetics but about cutting performance, bear in mind the primary has no role whatsoever in the cutting action of a plane. On a plane iron, behind the honed cutting edge it doesn't matter if the steel is dead flat, ground hollow, slightly curved out (a cambered bevel), or a succession of even or uneven grinds. The ONLY part doing the cutting is the very edge.

Now that I've reviewed the relevant pages in The Essential Woodworker some tips for next time you want to create a curved edge.

The best way to grind any new shape into the edge is to first do it 'flat', that is to grind straight into the edge. Then you work to create the bevel that matches that profile, whether it's straight or curved.

While you can grind a new profile entirely by eye, it takes a bit of practice to do it well and if you want an even result each and every time it's best to create a simple template with a curved edge that you can lay onto the iron and draw around with a marker3. This is done on the flat (non-bevel) side of the cutting iron in case that's not clear.

Some general observations on grinding and honing:

On any standard grinder running a normal grinding wheel great care must be taken not to overheat the edge, as Robert Wearing cautions. It's not a complete disaster if this happens, but always do your best to prevent it.

Realise that the closer you grind to the edge the thinner the steel is becoming, so it becomes more and more likely to overheat as the grinding approaches the edge (especially at the very corners4). Generally aim to stop grinding when there's a gap of very approximately 0.5mm between the new ground bevel and the edge — depending on grinder speed, wheel type, your confidence level, how often you can stomach stopping and dunking in water. Once you get good at this, and with regular cooling, you can grind to within 0.2mm successfully.

Since almost no honing jig allows for honing of a pronounced curved edge you pretty much have to do your honing of the bevel freehand. This is a great reason to start to learn to hone freehand; this can be difficult for some people (most?) but it's a lifetime skill and worth persevering with.

A secondary bevel can be TINY. The modern concept of a microbevel is merely a secondary bevel that's very very narrow. They work the same either way. It's just easier and faster to create a small one (barely a shiny line at the edge) and progress from there.

A primary + secondary is not the only way to go, especially now with the easy availability of diamond plates (especially inexpensive ones from China have opened up this area to be a viable option for anyone). The extremely good cutting action of diamonds mean it's no longer necessary to think of primary and secondary bevels, and potentially you can grind an iron once, or, accept the ground edge from the factory, and literally never grind again, for the lifetime of a tool, barring accidental damage.

Remember that a properly sharp edge is only created if two smooth surfaces meet, so the back should also be taken up to a high level. But don't bother wasting valuable workshop time by flattening much of it :-)

If you're not using a water-cooled or cold-running grinding system you must do something to cool the iron during any grinding process. The most efficient way is to dunk into water. Note: despite cautions specifically saying not to do this there's virtually no evidence dunking repeatedly into cool water does the steel any harm; this cooling method has been standard practice since before any modern commentator was born, and if it commonly caused an issue it would be widely known! Consider these cautions yet another example of modern hand-wringing, no matter the apparent authority of the source, and move on with your life.

Note that all advice relating to overheating an edge and then completing the initial edge creation manually (regardless if freehand or in a honing jig) is now obsolete if running a CBN wheel, even on a high-speed grinder. Nor does it apply to any water-cooled system.

1 In reality it doesn't matter if the honed angle is 28°, 30°, 32° (all the way up to around 40°, although that steep would be unusual.

2 This is a jack used in the traditional British way, i.e. a "roughing jack". These days many prepare their jack planes differently. (And I think in error, as it misses out on a very useful plane type for the hand-tool woodworker.)

3 Or alternatively you colour the whole end, then use the template to scratch a line onto the steel. This shiny scribed line is very easy to see as you check progress, and won't wear off like a drawn line can.

4 On a chisel this is very much not ideal, on a plane iron it's usually completely irrelevant — the corners don't do any cutting on almost all planes.