I am doing my best to only use simple notions, but the explanation will look very strange and indirect. We will start with geometry.

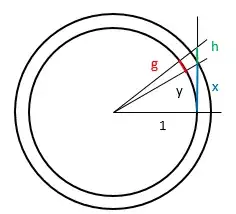

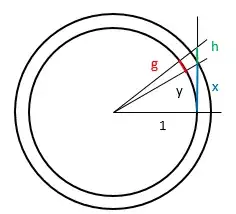

On the figure you see two right triangles, of basis $1$ and height $x$ and $x+h$ respectively. Note that $x$ and $h$ are line segments, while $y$ and $g$ arc circular arcs. We are particularly interested in the relation between the values of $y$ and $x$, which we will study by observing how the height difference $h$ makes the corresponding arc length $g$ vary.

By Pythagoras, the hypothenuses of the small triangle is $\sqrt{1+x^2}$, which is also the radius of the large circle. Then the arc facing $g$ on the larger circle has a length of $g\sqrt{1+x^2}$; if you straighten it, it becomes the base of the small outer triangle, which by proportionality has the length $(g\sqrt{1+x^2})\sqrt{1+x^2}$.

So we have established

$$\frac{g}{h}\approx\frac1{1+x^2}.$$

This relation is quite approximate in the figure, but if you make $h$ smaller and smaller, it becomes more and more accurate, because the arcs become more and more straight.

Actually, we just computed a derivative, i.e. the ratio of a variation of $y$ (from $y$ to $y+g$) over a variation of $x$ (from $x$ to $x+h$). This is a notion from calculus.

Now we want to express the relation between $x$ and $y$ and we will assume that it is of the polynomial type:

$$y(x)=a+bx+cx^2+dx^3+ex^4\cdots$$ without specifying the final degree. Using this formula, let us evaluate the ratio $g/h$, i.e.

$$\frac gh=\frac{y(x+h)-y(x)}h=\frac{a-a+b(x+h-x)+c((x+h)^2-x^2)+d((x+h)^3-x^3)+\cdots}h$$

For example, the cubic term gives, using a remarkable product

$$\frac{(x+h)^3-x^3}h=\frac{(x+h-x)((x+h)^2+(x+h)x+x^2)}h=(x+h)^2+(x+h)x+x^2.$$

If we again decrease $h$ so that it becomes neglectible compared to $x$, we obtain $3x^3$. Repeating this reasoning with all terms, you can check that we will get the polynomial expression

$$\frac gh=b+2cx+3\,dx^2+4\,dx^3+5\,dx^4+\cdots$$

We would like to compare it to the previous expression, which unfortunately is not in a polynomial form. We can achieve this goal by using the "geometric progression" formula.

Let us consider the numbers $(-x^2)^k$ and compute their sum for $k$ from $0$ to $n$:

$$S_n=1-x^2+x^4-\cdots(-x^2)^n.$$

Then if we multiply the sum by $-x^2$ and subtract, we obtain after a lot of terms cancellation

$$(1+x^2)S_n=1-(-x^2)^{n+1},$$ so that

$$S_n=1-x^2+x^4-\cdots(-x^2)^n=\frac{1-(-x^2)^{n+1}}{1+x^2}.$$

If $x^2<1$, then $(x^2)^n$ becomes smaller and smaller so that we can simplify

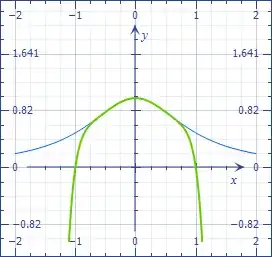

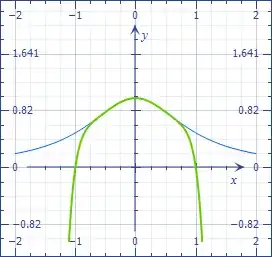

$$S_n=1-x^2+x^4-\cdots(-x^2)^n\approx\frac1{1+x^2},$$ and the larger the final degree, the better the approximation. The figure shows the matching of the polynomial of degree $10$ with the exact formula.

Now we are able to compare the formulas for $g/h$, and by identification,

$$b=1,c=0,d=-\frac13,e=0,f=\frac15,\cdots$$

Then, noting that $y(0)=0$, we also have $a=0$ and we establish the famous Gregory series,

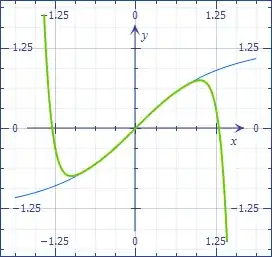

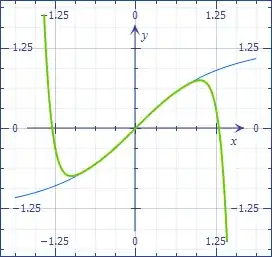

$$y(x)=x-\frac{x^3}3+\frac{x^5}5-\frac{x^7}7+\cdots$$

which is illustrated in the next picture (to degree $11$). It develops the so-called arc tangent function:

Finally, we can observe that when $x=1$, the arc $y$ covers an eighth of the circumference, hence the Leibnitz formula

$$\frac\pi4=1-\frac13+\frac15-\frac17+\cdots$$

The attentive reader may have noticed a little twist in the explanation. While obtaining the formula for $1/(1+x^2)$, we assumed that $x^2<1$, but later used $x=1$. For reasons that deserve many more explanations, the "polynomial" expression for $y(x)$ is still valid for $x=1$.