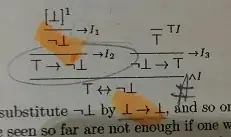

The first step ($\rightarrow I_1$ : top left) is :

i) $\bot$ --- assumed

ii) $\bot \vdash \bot$

iii) $\vdash \bot \rightarrow \bot$ --- from ii) by $\rightarrow$-Introduction

iv) $\vdash \lnot \bot$ --- from iii) by abbreviation : $\lnot P := P \rightarrow \bot$.

The second step ($\rightarrow I_2$ : bottom left) is only a "tricky" application of $\rightarrow$-Introduction : $A \vdash B \rightarrow A$.

To see that it is correct, we can use the Hilbert-style version of propositional logic.

It is a well-known fact that $A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$ is a valid logic law (in classical logic, it is a tautology).

Intuitively, it is so becuase, if $A$ is true, then the conditional $B \rightarrow A$ is also true.

In the Hilbert-style version of propositional calculus this formula is often an axiom.

Thus, from $\vdash A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$, if we assume $A$, then by modus ponens we can derive : $B \rightarrow A$.

The same fact can be "translated" into Natural Deduction with the possibility to "discharge" a formula $B$ whatever with an application of $\rightarrow$-Introduction :

$$\frac{A}{B \rightarrow A}$$

Conclusion : apply it with $\lnot \bot$ as $A$ and $\top$ as $B$ to get :

$$\frac{\lnot \bot }{\top \rightarrow \lnot \bot} (\rightarrow I_2)$$

The same for top right, with $(\rightarrow I_3)$.

Note

For an explanation, see Jan von Plato, Elements of Logical Reasoning (2013), page 22 :

There is a limiting case of a derivation in which an assumption $A$ is made. It is at the same time a derivation of the conclusion $A$ from the assumption $A$, as in:

<ol>

<li><p>$A$ : hypothesis</p></li>

<li><p>$A \rightarrow A$ : 1,$\rightarrow$-I</p></li>

</ol>

<p>In terms of the derivability relation, the hypothesis on line 1 can be written as $A \vdash A$ and line 2 as $\vdash A \rightarrow A$.</p>

<p>Consider as another case $\vdash A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$. Verbally, if we assume $A$, then $A$ follows under any other assumption $B$ :</p>

<ol>

<li><p>$A$ : hypothesis</p></li>

<li><p>$B \rightarrow A$ : 1,$\rightarrow$-I</p></li>

<li><p>$A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$ : 1–2,$\rightarrow$-I</p></li>

</ol>

<p>This does not look particularly nice: We have closed an assumption $B$ that was not made. But if we say that an assumption was used $0$ times, the thing starts looking more reasonable. [...] we can say that assumption $B$ in the derivation of $A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$ was used <em>vacuously</em>.</p>

In details, we have to compare the two following derivations :

(A) $\vdash A \rightarrow A$

i) $A$ - assumed

ii) $A \vdash A$

iii) $\vdash A \rightarrow A$ --- from ii) by $\rightarrow$-I.

(B) $\vdash A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$

i) $A$ - assumed

ii) $B$ --- assumed

iii) $A,B \vdash A$ --- from i) and ii)

iv) $A \vdash (B \rightarrow A)$ --- from iii) by $\rightarrow$-I

v) $\vdash A \rightarrow (B \rightarrow A)$ --- from iv) by $\rightarrow$-I.

I would like to write this as $$\frac{A\rightarrow (A \rightarrow B) A}{B \rightarrow A}\rightarrow I$$,

how come you don't write the $A \rightarrow (A \rightarrow B) $?

– Alexander Sep 20 '14 at 11:06