Partial answer

I put here my thoughts about this problem. Please excuse the lack of formalization if any.

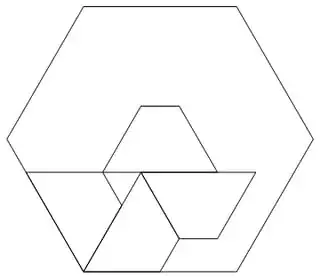

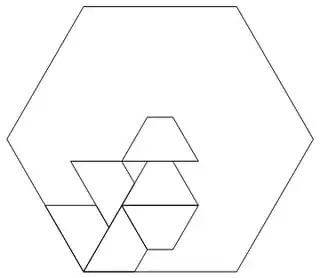

The possibility to cut a regular $N$-gon such that $N>4$ into congruent pieces such that the center of the regular polygon lies strictly inside one of the pieces is limited by the following facts:

(1) For $N>4$, the central angles $\alpha(N)$ of any regular $N$-gon are smaller than its inner angles $\beta(N)$. This can be easily checked, as $\alpha(N)=\frac{360}{N}$ and $\beta(N)=\frac{(N-2)*180}{N}$, so $\frac{\alpha(N)}{\beta(N)}=\frac{2}{N-2}$, which is lesser than $1$ for $N>4$

(2) Some regular $N$-gon is divisible in pieces $P$ only if one of the inner angles of $P$ divides exactly $\beta(N)$. Otherwise, there would be created an "empty" space that can not be filled with pieces $P$

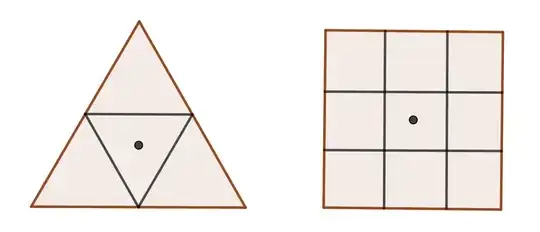

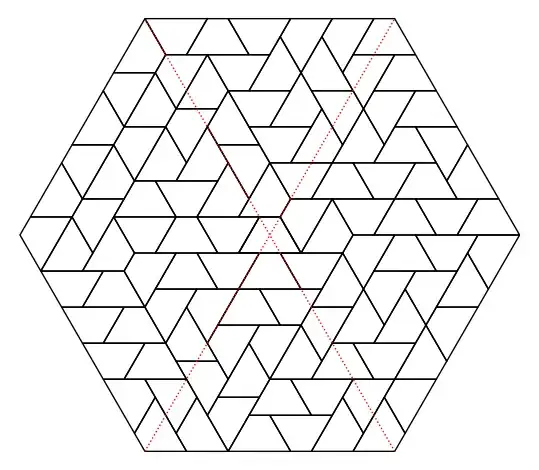

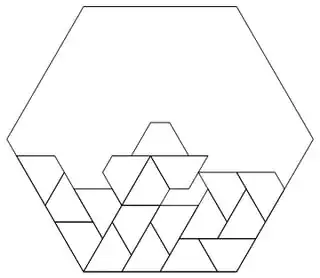

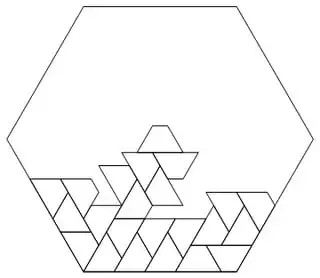

This facts prevent some regular $N$-gon such that $N>4$ to be cut in pieces $P$ such that $P$ is some regular polygon. For any regular polygon $P$ of $N>4$, fact (1) would imply the creation of some "empty" space by the polygons $P$ adjacent to the polygon $P$ with the center of $N$ strictly inside, that can not be filled with polygons $P$. Fact (2) let us discard also cutting any regular $N$-gon with squares, as no $\beta(N)$ is divisible by 90º; and finally, it can also be discarded cutting any regular $N$-gon with equilateral triangles for the same reason, with the exception of the hexagon; but in this case, the symmetries of the bisection of the inner angles disallows that the center of the hexagon lies strictly inside one of the triangles.

It would remain to show that using some non-regular piece $P$ is not possible for any regular $N$-gon. Fact (2) forces some inner angle of any piece $P$ to be greater than 90º (and thus such that it does not divide $\beta(n)$), which I believe that eventually leads to the creation of "empty" spaces that can not be filled with pieces $P$, but I am still working on a more formal proof.