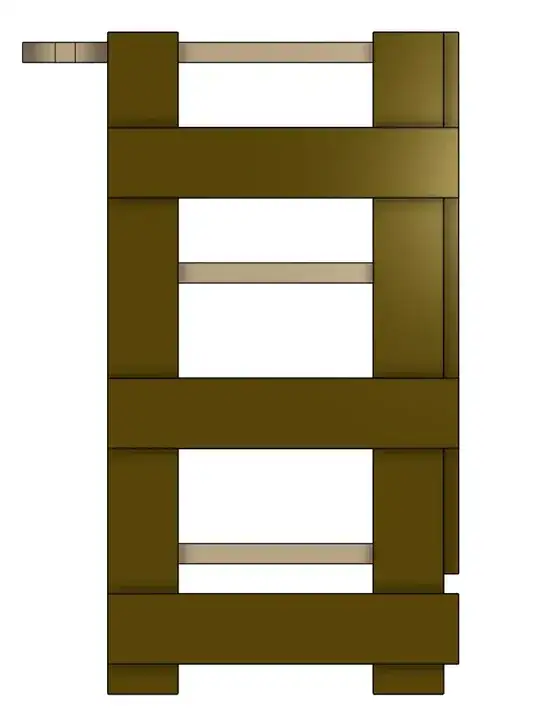

This is an unconventional design in certain ways, and without a formal box exterior, and either a solid back or some form of diagonal bracing it might seem like it would be prone to racking but I think this is only if viewed superficially1.

Screws are a pretty firm fastener, allowing much less flex than nails for example, and the more of any fastener you add the greater the overall strength and stiffness.

The way I am interpreting how this will be put together there will be 10 screws per shelf at minimum, but I don't see any reason not to use two screws at every intersection which means 14 per shelf, so 42 screws overall. I don't see any reasonable force that can break free or snap over 40 screws. It may not be the stiffest thing ever made, but it doesn't have to be and if it's screwed together well I'm certain it will be more than strong enough for what it needs to do2.

The real challenge here

Because there's no formal joinery here it doesn't hold itself up, and no part rests upon or intersects with another. So holding the various pieces in correct alignment initially is going to the hardest part. Some careful marking out, numerous clamps and, I would recommend, a couple of temporary clamping blocks, are going to be needed.

Once the initial pilot holes are drilled it becomes relatively straightforward to assemble this, after the clearance holes and countersinks/counterbores are all done (assuming they're not drilled in a single operation using a combination countersinking bit).

I was going to give a suggestion for a small change to the design to improve strength, but I just don't think it's necessary if this is completely (and properly) screwed together.

See the following Answer if you're an all woolly on where you need to drill pilot holes and clearance holes (see the bottom of this Answer.

Might as well also link to this on screws and end grain given the prevailing belief that they're so weak you can't rely on them, Endgrain screw withdrawal force. I don't know about you, but I consider a loss of only 25% of holding power no big deal, especially when it can be compensated for in multiple ways and they can all be used together.

1 This can't be considered in any way other than as a complete system, a single unit. The examples given in woodworking books demonstrating racking show e.g. a cabinet box without a back, which is prone to parallelogramming when any force is exerted from the side, but when the back is added the potential for that goes away. This is no different in that its resistance to racking must be considered as a whole, not looking at any one section of it in isolation.

2 I have a couple of shelving units of very different types in my home that don't have solid backs and are not braced diagonally instead. When they're slid about with no contents removed (which we're not supposed to do, but most of us do anyway) they DO rack. But when they're sitting there statically holding their contents, like 99.9999% of the time, they're perfectly stable. As they have been since about 1980.....

3 And that is moving the horizontals on the end frames inboard of the vertical members, and repositioning them so one edge aligns with the sheves. This would allow for more screws to go into the end grain of the shelves, There's a big change in the aesthetics,