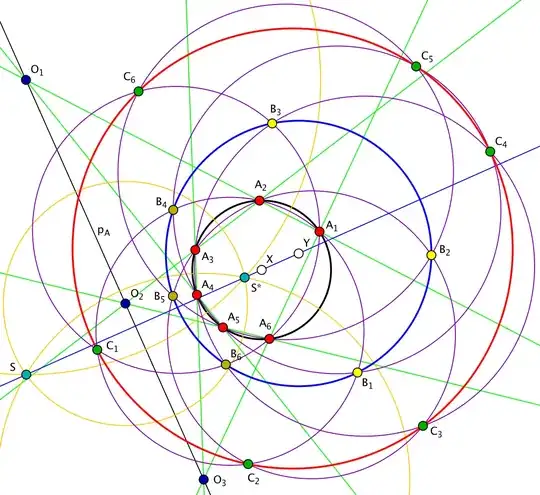

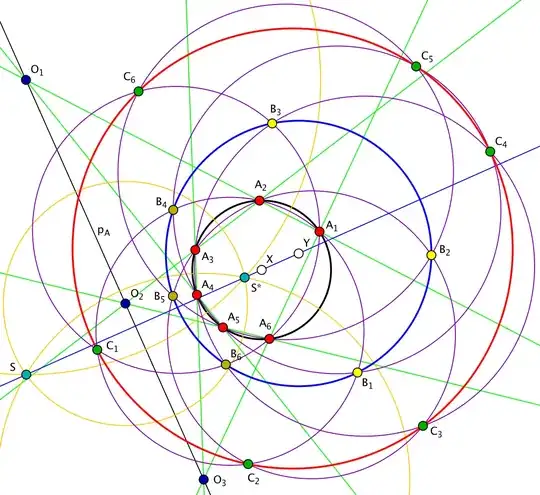

By Pascal's theorem the three intersection points $$O_1 = A_1A_2

\cap A_4A_5 \, , \,\,\, O_2 = A_2A_3 \cap A_5A_6 \, , \,\,\, O_3 =

A_3A_4 \cap A_6A_1$$ lie on a common line (the Pascal's line)

$p_A$. Draw the three circles $k_1\,, \,\, k_2\,,\,\, k_3$

centered at the points $O_1,\,O_2\,O_3$ respectively and each of

them orthogonal to the circle $k_A$ (the circle passing through

the points $A_1, A_2, A_3, A_4, A_5, A_6$). Then, $k_1, k_2, k_3$

intersect at two common points $S$ and $S^*$, i.e. the circles

$k_1, k_2, k_3$ are coaxial (have a common radical axis, passing

through the points $S$ and $S^*$, and orthogonal to the Pascal

line $p_A$).

From now on, by $k(ABC)$ I denote the unique circle (or a straight

line) passing through the points $A, B, C$.

Lemma 1. Let $k_B$ be a circle different from $k_A$. Take an

arbitrary point $B_1$ from $k_B$ and draw the pair of circles

$k(B_1A_1A_2)$ and $k(B_1A_4A_5)$. Then the second intersection

point $B_4 (\neq B_1)$ of $k(B_1A_1A_2)$ and $k(B_1A_4A_5)$ also

lies on $k_B$ if and only if $k_B$ orthogonal to circle $k_1$.

Proof: By construction of circle $k_1$, if one performs an

inversion with respect to $k_1$, then $A_1$ is mapped to $A_2$ and

$A_4$ is mapped to $A_5$. Thus, circle $k(B_1A_1A_2)$ is mapped to

itself and is therefore orthogonal to $k_1$. Analogously, circles

$k(B_1A_4A_5)$ is also orthogonal to $k_1$. By the radical axis

theorem applied to the circles $k_A, \, k(B_1A_1A_2)$ and

$k(B_1A_4A_5)$, the three radical axes $B_1B_2, \, A_1A_2$ and

$A_4A_5$ intersect at a common point, which is $O_1 = A_1A_2 \cap

A_4A_5$ -- the center of circle $k_1$. Therefore, point $B_1$ is

mapped to $B_4$ under the inversion with respect to circle $k_1$.

Consequently, if $k_B$ is orthogonal to $k_1$, since $B_1 \in k_B$

its inversive image $B_4$ also lies on $k_B$. Conversely, if both

$B_1$ and $B_4$ lie on $k_B$, then the circle $k_B$ is orthogonal

to $k_1$.

Lemma 2. Let $B_1$ and $B_2$ be two different points in the

plane. Let the pair of circles $k(B_1A_1A_2)$ and $k(B_1A_4A_5)$

intersect again at the second point $B_4 (\neq B_1)$, and let the

pair of circles $k(B_2A_2A_3)$ and $k(B_2A_5A_6)$ intersect again

at the second point $B_5 (\neq B_2)$. Then the four points $B_1,

B_2, B_4, B_5$ lie on a common circle $k_B$ if and only if $k_B$

is orthogonal to the three circles $k_1, k_2, k_3$.

Proof: Let $k_B$ be a circle passing through points $B_1$ and

$B_2$. By Lemma 1, points $B_4$ and $B_5$ also lie on $k_B$ if and

only if $k_B$ is orthogonal to both circles $k_1$ and $k_2$.

Therefore, the radical axis $SS^*$ of $k_1$ and $k_2$ passes

through the center of $k_B$ whenever $k_B$ is orthogonal to $k_1$

and $k_2$. However, by construction, $SS^*$ is a common radical

axis for all three circles $k_1, \, k_2$ and $k_3$ which means

that $k_B$ is orthogonal to $k_3$ as well.

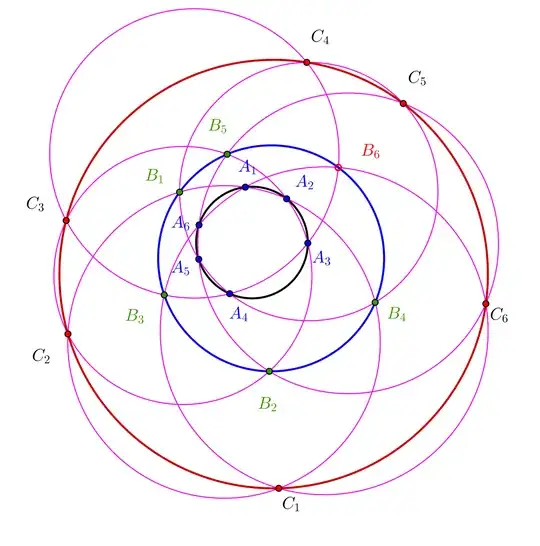

Corollary 3. In the setting of Lemma 2, let the four points

$B_1, B_2, B_4, B_5$ lie on a common circle $k_B$. If $B_3$ is

another (arbitrary) point on $k_B$, then the second intersection

point $B_6$ of the pair of circles $k(B_3A_3A_4)$ and

$k(B_3A_6A_1)$ also lies on $k_B$.

Proof: Follows directly from Lemma 2.

From now on, I am in the setting of Lemma 2, Corollary 3 and the

statement of the original problem, where points $A_1, A_2, A_3,

A_4, A_5, A_6$ lie on the circle $k_A$ and the points $B_1, B_2,

B_3, B_4, B_5, B_6$ lie on the circle $k_B$. In the notations of

the original problem $C(A_6,A_1)$ is the circle $k(B_3A_6A_1)$,

the circle $C(A_1,A_2)$ is the circle $k(B_1A_1A_2)$, the circle

$C(A_5,A_6)$ is the circle $k(B_2A_5A_6)$ etc.

Lemma 4. The four lines $B_1B_4,\, B_2B_5,\, A_2C_2$ and

$A_5C_5$ intersect in a common point $D$.

Proof: Define $D$ as the intersection point of the lines

$B_1B_4$ and $B_2B_5$. Let us look at the three circles $k_B, \,

C(A_1A_2)$ and $C(A_2,A_3)$, where $C_2$ is the second point of

intersection of $C(A_1A_2)$ and $C(A_2,A_3)$, the one that is

different from $A_2$. Then their three corresponding radical axes

$B_1B_4,\, B_2B_5$ and $A_2C_2$ intersect at the common point

$D$. Analogously, the three circles $k_B, \, C(A_4A_5)$ and

$C(A_5,A_6)$ define the three radical axes $B_1B_4, \, B_2B_5$ and

$A_5C_5$ which intersect at the common point $D$.

Lemma 5. The four points $A_2, A_5, C_2, C_5$ lie on a common

circle $k_{25}$.

Proof: As a consequence of Lemma 4, the two chords $B_1B_4$ and

$A_2C_2$ of the circle $C(A_1,A_2)$ satisfy $$B_1D \cdot DB_4 =

A_2D \cdot DC_2.$$ Similarly, again by Lemma 4, the two chords

$B_1B_4$ and $A_5C_5$ of the circle $C(A_4,A_5)$ satisfy

$$B_1D \cdot DB_4 = A_5D \cdot DC_5.$$ Consequently

$$ A_2D \cdot DC_2 = B_1D \cdot DB_4 = A_5D \cdot DC_5$$ which is

possible if and only if the four points $A_2, A_5, C_2$ and $C_5$

lie on the the same circle, we call $k_{25}$.

Lemma 6. The four points $C_5, \, C_6, \, C_1$ and $C_2$ lie

on a common circle, we call $(C)$.

Proof: It follows from Lemma 5 and Miquel's theorem applied to

the circles $C(A_5,A_6), \, C(A_6,A_1), \, C(A_1, A_2), \, k_{25}$

and $k_{A}$.

Finally, we can apply Lemmas 5 and 6 consecutively first to points $A_3, \, A_6, \, C_3, \, C_6$ and second to points $A_1, \, A_4, \, C_1, \, C_4$ in order to show that first the points $C_6, \, C_1, \, C_2$ and $C_3$ lie on a

common circle, which has to be again $(C)$ and second that the

points $C_1, \, C_2, \, C_3$ and $C_4$ also lie on a common

circle, which is $(C)$.