(1.) Why didn't Fraleigh state the result in the direct form like in my title? Why state it with the negations and then prove the contrapositive? Isn't this extra unnecessary work?

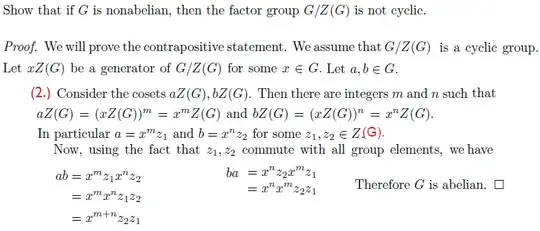

(2.) How do you envisage and envision to consider the cosets $aZ(G), bZ(G)$?

I know we presupposed $G/Z(G)$ is cyclic for the proof.

(3.) If $G/Z(G)$ is cyclic then $G/Z(G)$ has one element. What is it?

(4.) What's the intuition?